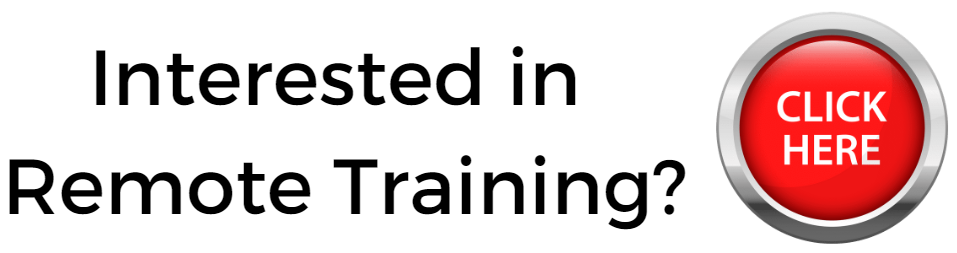

The infrasternal angle (ISA) is an angle formed by the cartilage of the lower ribs and the twelfth thoracic vertebra. This angle spans a spectrum from narrow to wide. Generally, individuals with an ISA > 90 degrees are considered “Wide”, while < 90degrees are considered “Narrow”. It has been our experience through assessments at our facility that most “Narrows” fall between 80-90 degrees, while the “wide” guys fall somewhere between 95-105 degrees. The ISA is a representation of a person’s breathing strategy as well as the balance of the internal and external oblique muscles, and the position of the pelvis.

It’s important to note that although we have had athletes that present as a Narrow, they have excelled on the mound with the mechanics generally found in Wide athletes and vice-versa. So, there are no absolutes in this business. However, the ISA can still tell us a lot about an athlete’s “preferred strategy” both in the weight room and on the mound. Let’s get into it…

First, here’s a great video by PT Bill Hartman on assessing the ISA.

Assessing Infrasternal Angle

For the scope of this article, I will focusing more on training strategies in the weight room. First, let’s talk a bit about what we mean by preferred strategies when referring to a Wide vs. Narrow ISA.

Narrow (< 90 degrees) – The narrower ribcage is biased towards external rotation in the lower half as well as being more compressed laterally in the frontal plane. This allows more room for movement from anterior to posterior.

Benefits: Narrow ISAs are usually more elastically driven and can better utilize their connective tissue (i.e., tendons) to produce movement than their musculature. This produces a more reactive movement, which is usually more energy efficient.

Downside: Less musculature and faster movement give the athlete more of a tendency towards injury.

Characteristics / Traits: Typically tend to be more elastic or reliant on their connective tissue for movement than on muscle. Thrive while training plyometrics and lighter loads explosively and are generally less efficient under deeper, heavier loads/volume.

Narrow / Elastic-Driven: Jacob DeGrom

Wide (>90 degrees) – The wider rib cage is generally biased toward internal rotation in the lower half, as well as compression within their body occurring in the sagittal plane (front to back). This contributes to a wider physique laterally, making it more difficult for them to move their limbs when coming down the mound.

Benefits: The bias to internal rotation allows the lower half to screw into the ground at foot plant more efficiently and produce high forces for a longer duration. With less risk of injury. This is why they love lifting heavy. It’s their innate ability to “grind out reps”.

Downside: They take longer to produce those forces, making it less energy efficient.

Characteristics / Traits: Generally, have more of a muscular reliance. Thrive during heavy lifting, deeper movements and are generally less plyometrically proficient.

Wide / Muscle-Driven: Garret Cole

Athletic Testing

Sometimes it can be hard to distinguish a “wide / muscular-driven” athlete from an “narrow / elastic-driven” athlete due to the fact that test results may be very similar. They will however, achieve similar outputs by using different strategies. We test our athletes using 2 methods:

-

- CMJ / Squat Jump

- Continuous Pogo Jump

1. CMJ / Squat Jump – The Countermovement or “CMJ” jump can give us some insight to not only how elastic an athlete is, but how well they use the elasticity they already have. After testing, we use a few determining factors to program either unilateral strength or plyometric drills based on where they lie on the Force-Velocity curve.

Wide: Look for a deep countermovement jump, where the individual can access their big, powerful musculature of their lower body to achieve maximum height. Most times, Squat jump height will fall within 10% of the more elastic-based CMJ jump.

Narrow: Look for a shallower depth squat, but faster time to takeoff than a wide. CMJ jump height will generally fall >10-15% of the more muscular-driven squat jump.

CMJ Jump

0

Squat Jump

2. Continuous Pogo Jump – This test evaluates pure elasticity and also the ability to rely on an athlete’s connective tissue to produce movement. This is where we really see a Narrow pitcher thrive. Once again, Reactive Strength Index (RSI) results may be very similar, however, how they achieve these outputs is much more telling.

Wide: Typically spend more time on the ground and rely on a greater jump height to execute their RSI score.

Narrow: Typically have slightly lower jump heights and rely on faster contact times to execute their RSI score. Each jump will also have a tendency to be slightly higher due to the higher level of elasticity allowing the athlete to use the previous jump height to load the next effort.

Continuous Pogo Jump

Programming

“One Size Doesn’t Fit All”

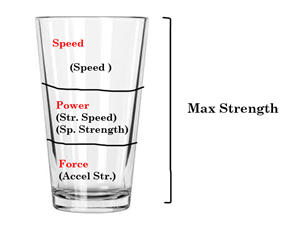

Let me start by saying, “Max strength is the glass that holds all other types of strength”.

There are qualities that traditional strength movements develop that every individual needs regardless of structure. As a result, both Wide and Narrow athletes need to train max strength. The key is that it’s all about the timing and dosage.

Strength-wise, training the big lifts at 80-90% 1RM (max strength), is great for some athletes (Wides), but if trained with higher volumes too frequently fills up the wrong bucket for others (Narrows) .

Giving each athlete the right amount of strength at the right time to increase durability and maximize strength is the key. The right time means NOT dosing the Narrow and elastically driven individuals with high-intensity methods throughout the entire year.

Also, most Wide’s architecture is built for lifting heavy weights and grinding through reps that produce tremendous amounts of internal rotation and compression.

This can be “the kiss of death” for a narrow athlete whose structure lends itself to being springy and elastic and spending less time on the ground; a structure that excels in quickness and the ability to move through higher degrees of rotation. As a result, most of the year, lifts are loaded to approx. 70-80% 1RM with only a few times a year being spent on higher loads.

Periodization

Early off-season training…

“Give them what they need”

Tissue Prep – The early off-season is the best time to give each archetype a dose of what they need. “Early” is the key word here due to the fact that focusing on training what the athlete needs will generally cause their key point indicators (what they’re already good at) to go down/decrease for a bit. The fact that athletes do not need to be at their best for a few months makes it an opportune time. This means:

Narrow – Approx. 4-8 weeks of unilateral “high load” (75-85% 1RM) for a narrow to help develop a better foundation of max strength to help add to their already elastic properties.

Wide – Approx. 4-8 weeks of higher volumes of quick, extensive plyometrics to add to a wide’s tendency towards slower force-based strength.

We will re-introduce these methods in small doses throughout the year when appropriate in order to “maintain” what we have built- that being strength/stiffness in a narrow or elasticity / reactive ability in a wide.

Narrow – SSB RFESS

Wide – Lat Hurdle Hop to Heiden

As always, with athletes under the age of 16 or less than 2 years of strength training experience, we will train max strength all year. This helps to build a large foundation of strength and “raise their floor of strength” before trying to get fast with it prematurely.

Reassessing – By reassessing periodically, we can see if training is moving us in the right direction and adjust if necessary. This would mean better “strength / stiffness” to a narrow and “elasticity / reactive” ability to a wide. The following provides a brief summary of what to expect when re-assessing:

Narrows

CMJ – Look for:

-

-

- Expect jump height and peak power to go up.

- Time to takeoff goes up- but only slightly

- Countermovement depth gets a bit deeper

-

Ideally, by this point in the year, these athletes have improved their strength, enabling them to achieve higher jump height and overall power while only sacrificing minute amounts of time to take off, which we will train back into them in the second half of the off-season.

Continuous Pogo Jump – Look for:

-

-

- Slightly decreased ground contact time.

- Overall Improvement in RSI through increased jump height.

-

Wides

CMJ – Look for:

-

-

- Jump height goes up.

- Time to takeoff gets quicker

- Countermovement depth gets a bit shallower

-

Ideally, by this point in the year, these athletes have improved their elastic qualities, enabling them to achieve higher jump height and power through a faster time to takeoff. This involves them moving through the loading phase of the CMJ faster and slamming on the brakes rapidly.

Continuous Pogo Jump – Look for:

-

-

- RSI improvements primarily through quicker ground contact time

- Jump height stays the same or even may decrease a bit

-

While I typically don’t load bilaterally or with with higher intensities. I challenge them to produce as much force as possible in a short time frame, in a shorter range of motion with light loads. I expose these individuals to progressing volume in extensive plyometrics, put them in unilateral positions for both lower and upper body training, and also expose them to movements that involve rotation, such as crawling, rolling, and gymnastic activities.

Mid to Late Off-season…

“re-introduce what they’re good at”

In the second half of the off-season, after we have hopefully created some significant changes, we want to start training each athlete with more of what they are better at again.

Narrows

-

- Avoid high-load bilateral exercises that will force the athlete into excessive internal rotation and compression.

- Utilize staggered and split stances with lower-body movements.

- Most of the year, focus on the speed of movement rather than the intensity of movement.

- Allow upper-body training movements to include rotation

- Utilize more elastic-based, single leg movements when training plyometrics

Wides

-

- Allow these athletes to get back under some higher intensity load from a lower and upper body training perspective. While we personally do not bilateral squat our athletes, if it must be done- these are the guys that can do it …

- Allow for more time to generate force with our faster movements and load them slightly heavier than the Narrow and Elastic program.

- “Peak” by hitting high-intensity movements (1–3 rep max) close to the season. I believe this not only creates physiological benefits but also psychological benefits, so they “feel” their strongest heading into a season.

Summary

It’s important to remember that every athlete’s strategy is different. And, while every athlete leans more to either side of the Force-Velo curve, that being Muscular driven (wide) or elastic-driven (narrow), it’s important to take the ISA and its training preferences into consideration when creating training programs.

See ya’ in the gym…

By Nunzio Signore

You live too far to train with us in-house at RPP? You can now train with us on a REMOTE basis.